Governance As A Mirror 3/3

Who Holds the Line?

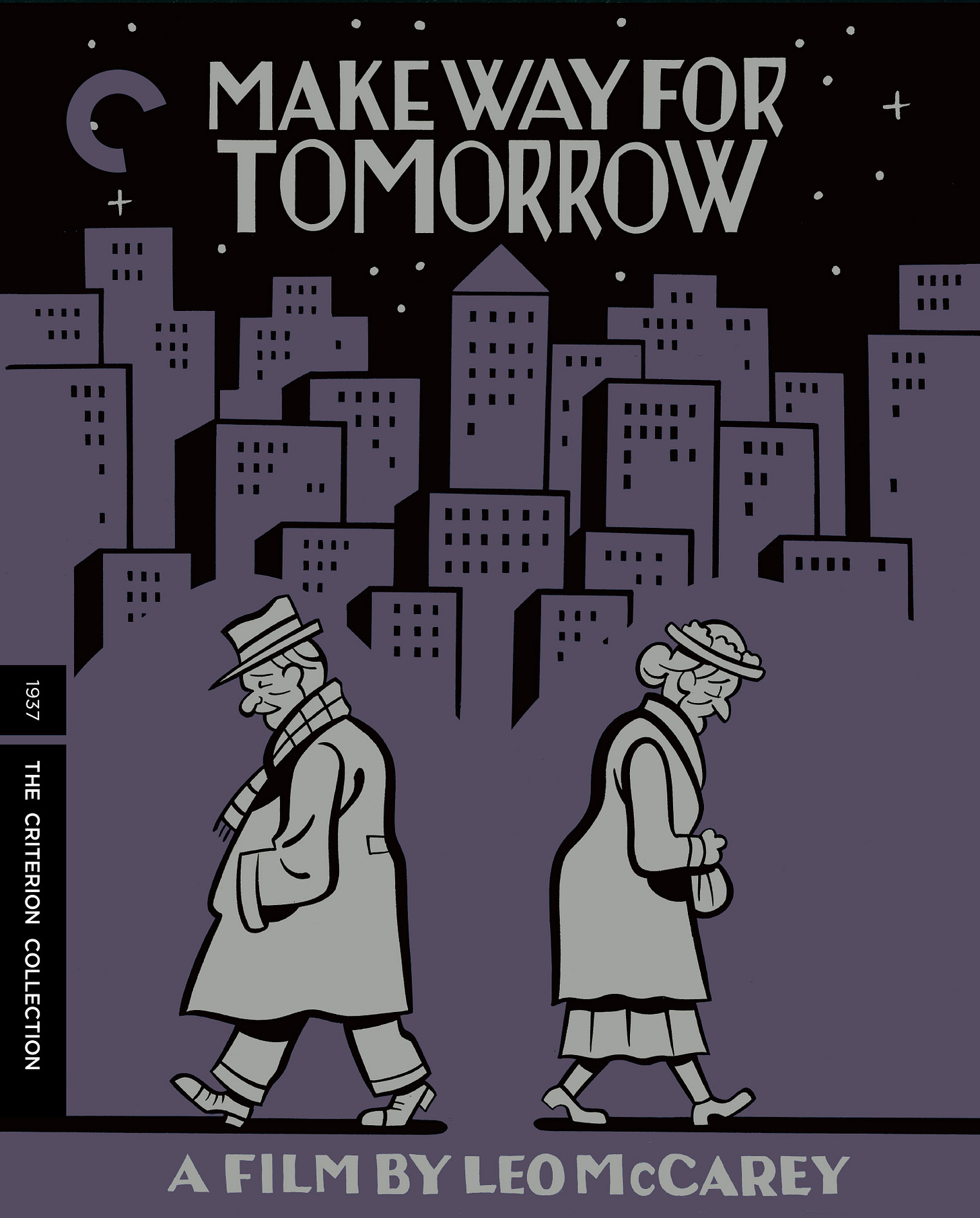

Make Way for Tomorrow (1937) is a rarely cited yet emotionally searing Depression-era film that explores familial obligation, emotional endurance, and dignity amid institutional abandonment. Directed by Leo McCarey, the film tells the story of an elderly couple forced apart when their children, citing logistical and economic constraints, choose not to care for them together. What unfolds is not melodrama, but quiet devastation. Often described as “the most devastating film you've never seen,” it has become a prophetic text for those asking what happens when systems fail and people retreat.

There is a moment that lands like prophecy. Displaced from their home and treated as burdens, the couple shares a final afternoon together. Institutions have failed them. Their adult children avoid them. The system forgets them. But in that quiet moment—fragile, unglamorous, real—they offer each other something different: presence. Not through policy. Not through predictive analytics. Through mutual care.

This is the kind of self-governance no dashboard can measure.

In this final post of the Governance Mirror series, we ask: Who holds the line when institutions abandon their role? Governance is not just an operational function. It is not just an audit trail. Governance lives in decisions made under pressure, in refusals to look away, in everyday courage. The real question is not what AI models forecast or which dashboards we build. The question is: Who pauses when the incentives say accelerate? Who says no when momentum demands yes?

We explore governance not as structure alone, but as behavior—behavior that resists ethical erosion.

Governance Lives in Behavior

Governance is frequently treated as a structural artifact: policies, audits, and architecture. But its most potent form is behavioral. Even in a world of automated systems, the final link in the decision chain is often a human. A model is reviewed. A score is accepted. A decision is escalated—or not. Gary Marcus (2019) emphasizes that even the most capable AI requires human interpretability and oversight to prevent cascading failure. Structure sets the conditions, but humans exercise judgment. That judgment is governance.

In high-risk domains, this means integrating governance into design protocols via ethical review boards, model interpretability audits, scenario planning, and escalation checklists. These aren’t procedural afterthoughts; they are governance in motion.

Accountability, then, is not solely what’s codified in documents. It’s enacted in the hesitation before the click. In the moment someone chooses not to escalate. These uncelebrated micro-decisions form the last mile of governance, and they are the most human.

Pause Is Not Passivity

In tech and policy environments, pausing is often conflated with indecision or inefficiency. But a deliberate pause is a form of strategic discipline. It is a site of resistance where systems default to speed. Amy Webb (2022) argues that foresight requires slowness in a culture addicted to acceleration. That means leaders must normalize moments of pause not as weak points, but as intelligence checkpoints (Haskell, 2025).

Consider how quickly values get sidelined: quarterly metrics, feature releases, or stakeholder demands. In these high-velocity contexts, reflection can seem like friction. But friction is the cost of alignment. Pausing allows for course correction. It gives space to re-center values before deployment becomes drift (Haskell, 2025).

This is the pivot point. In Driving Your Self-Discovery, pause becomes the fulcrum of discernment. It transforms behavior into leadership. It is the space in which ethical self-regulation becomes possible.

Naming What Others Avoid

AI-anomia isn’t just technical misalignment. It’s a breakdown in our collective ability to name what matters ethically, precisely, and coherently. As language collapses under euphemism and abstraction, so too does courage. If no one names the harm, the harm becomes normalized. If the metrics are vague, no one is accountable. If no one names the cost, the cost is displaced.

To hold the line is to call attention to the unspoken: unmodeled harm, extractive logic, performative alignment. Sometimes it’s questioning a default pattern or behavior. Sometimes it’s delaying a launch. Sometimes it’s refusing a contract. But it is always an act of visibility.

In her book The Quantified Worker, Ajunwa (2023) describes this collapse poignantly: we no longer just work at home; we live at work. Surveillance has become ambient, justified by efficiency, and embedded within wellness programs, biometric assessments, and algorithmic reviews. The psychological toll is immense. Silence becomes complicity.

Naming restores interpretive agency. It reclaims the right to say: “Not like this.”

Visibility is not only a moral stance—it is a design imperative. Institutions that formalize dissent channels, maintain decision logs, and surface anomalies in regular retrospectives transform ethical perception into operational muscle. Without such scaffolding, insight stays personal, never institutional.

Who Gets to Hold the Line?

Too often, the burden of integrity is pushed downward. Junior staff, external reviewers, and impacted communities—these groups are expected to raise concerns but are rarely given the power to act on them. Meanwhile, those in senior leadership float above consequence, buffered by abstraction, policy, or role distance.

Real governance is not about proximity to the boardroom. It’s about proximity to the problem itself, and its consequences.

If your decisions affect real people, you hold a line—whether you acknowledge it or not. The question is: Are you holding it with integrity, or looking away while someone else pays the cost?

This dynamic is not new. Henry Ford’s sociological department, in the early 20th century, offered immigrant workers a path to American citizenship—if they submitted to lifestyle surveillance and ideological conformity. As historian Stephen Meyer (1981) documents, Ford's model of governance blurred labor, morality, and data collection to enforce control. It was not productivity alone that motivated datafication. It was social control, masked as opportunity.

Today, many employers walk that same line. Wellness programs collect health data not by coercion, but through ostensibly voluntary participation, even though opting out often carries professional cost. Governance, framed as care, becomes a mechanism of surveillance. As Ajunwa (2023) notes, consent in these contexts is largely illusory: it’s a choice under pressure. From biometric wellness programs to algorithmic performance scoring, governance today is not about care. It’s about control. Pausing and reflection will soon become the greatest act of radical self- and organizational care precisely because the system trains us to never stop moving, questioning, or resting.

Holding the line, then, requires recognizing when governance becomes a proxy for control. And choosing, still, to resist.

How do these consent loopholes persist? What kinds of regulatory scaffolding—beyond notice and consent—might realign governance with care rather than control?

Building a Culture That Holds

Institutions don’t lose their way all at once. They falter through a gradual series of “forgettings.” Incentives, when misaligned, reward oversight and suppress dissent. Amy Webb argues that strategic foresight must be institutionalized, not just personalized. The same is true for ethical resistance.

To build cultures that hold the line, pauses must be normalized. Dissent must be seen as a creative contribution. Emotional labor—especially the courage to name dissonance early—must be valorized as a leadership competency.

These are not massive interventions. One small recalibration. One delayed approval. One act of refusal. These are how governance stays alive, effective, and impactful.

Closing Reflection

In Make Way for Tomorrow, governance failed. But love did not. That final moment—a walk, a train, a goodbye—was not big. It was dignified. It held.

So much of today’s governance failure stems from our unwillingness to hold discomfort long enough to let values catch up with action. What if governance was redefined not by what gets optimized, but by who is willing to pause?

What systems are you part of that depend on unspoken judgment? Where is hesitation treated as a liability instead of leadership?

Governance does not begin with systems—it begins with signals. With what we see, what we name, and what we choose to stop. To interrupt a pattern (with intention), to hold a design choice, a human choice, and a future choice—all at once.

Recommend This Newsletter

If this sparked a pause, share it with someone who is still trying to hold their complexity in a world that keeps asking them to flatten it. Lead With Alignment is written for data professionals, decision-makers, and quietly courageous change agents who believe governance starts with remembering.